Breathing for Flutists, According to Arnold Jacobs

Arnold Jacobs was principal tuba for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for 44 years. He inspired countless musicians to breathe more freely and produce a better tone. Flutists have benefitted from Arnold Jacobs’ teaching perhaps more than any other instrumentalist.

Although it may seem odd, playing the tuba and the flute requires about the same amount of air. Of the wind instruments, the flute is unique because the player does not have a mouthpiece in or on the mouth. We exhale air over the lip plate, but there is no resistance from the instrument. The tuba has the largest mouthpiece and the least resistance of the brass instruments. Opposites in size and sound, the flute and tuba are similar in the amount of air needed to play them.

Arnold Jacobs in Flute Talk

In one of the most requested and referenced articles in the history of the magazine Flute Talk, Arnold Jacobs’ work is explained. “The Dynamics of Breathing with Arnold Jacobs and David Cugell, M.D.” by Kevin Kelley is full of helpful information.

The article describes Jacobs’ idea that the best breathing is the kind you do naturally. He argues that the body has an innate wisdom for finding the most efficient air exchange. By paying attention to the natural breath, we can find more air for playing the flute (or tuba or any other instrument.)

Arnold Jacobs also talks about why talking about the diaphragm, an involuntary muscle, is not helpful when discussing breathing. Rather, he encourages us to think about the intercostal muscles.

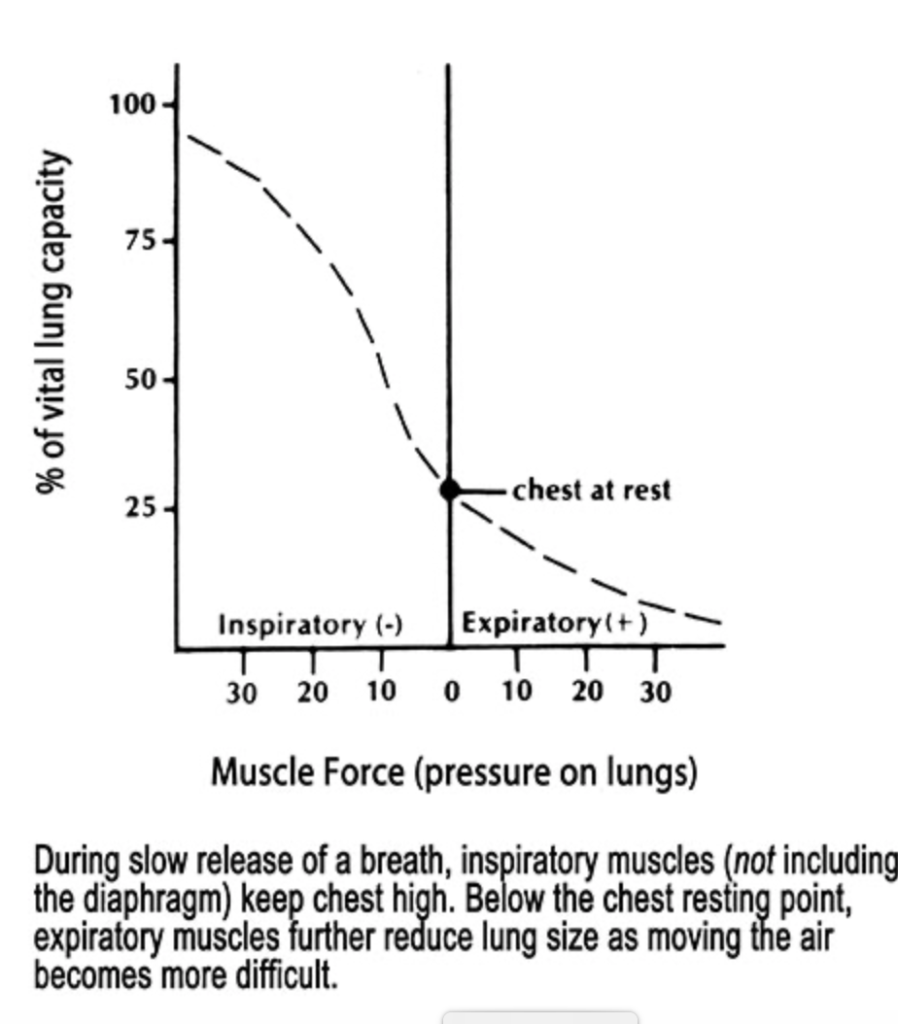

When we take a deep breath and play a note on the flute, the first thing we have to do is control the exhale with the intercostal muscles. Otherwise, the air pressure would cause the air to be expelled all at once, like a sigh. Once the air pressure in the lungs is the same as the air pressure outside, the muscles must contract to continue the air flow.

Breathing, So Simple and Yet So Complicated

For wind players, the breath is the sound. It is not possible to play a note without air. Nonetheless, we are breathing all of the time, even when we are sleeping, and have no active control over the lungs.

Arnold Jacobs encourages us to think about wind, rather than pressure. If we concentrate too much on “supporting” the air, we risk tightening muscles and causing a constricted sound. Rather, think about the air and where it is going, how the wind creates phrases and sound.

In the end, we have to get out of our body’s ability to control air naturally. If we work against our bodies by trying to force the air, the music will suffer. We must strive to understand how the respiratory system functions and work within its design. True freedom of movement and music follows.

More On Breathing

The Alexander Technique offers another way to think about natural breathing. Body Mapping offers insights into the ways our brains interfere with the function of the body to create pain.

I highly recommend Lea Pearson and Amy Likar, flutists who are experts in Body Mapping. Lea’s book Body Mapping for Flutists: What Every Flute Teacher Needs To Know About the Body is required reading.

No comments.